Louisiana freshman Senator John Kennedy made waves on Friday telling WVUE that “(Stop and Frisk) worked in New York. It’s the only way I know left to get the guns and thugs and dopes off the street. We got young people killing young people and now other citizens, and the reason is they got these guns, and until you get the guns you’re not going to stop it. The criticism of it is it’s racial profiling. No, not when it’s done correctly. When it’s done correctly, race has nothing to do with it.”

But Kennedy is wrong. New Orleans should want nothing to do with stop and frisk, and here’s why.

Let’s start with Kenendy’s first sentence from the above paragraph.

New York has had an undeniably miraculous drop in crime since the early 1990s with the city’s murder rate dropping from 30.7 per 100,000 to 3.9 in 2014. What’s less clear is the degree to which stop and frisk influenced that change.

Murder was falling long before stop and frisk was ramped up in New York in the early 2000s and murder kept falling after stop and frisk peaked in 2011 (see the chart from the ACLU here).

First, to assess Kennedy’s assertion that it worked in New York we have to ignore the unconstitutionality of parts of stop and frisk as New York practiced it and focus entirely on ‘in what circumstances might it have worked there?’.

A 2016 paper by David Weisburd is the most recent academic effort to develop a record on whether stop and frisk works. Weisburd reviewed stop and frisk at a micro level and found that there’s evidence that it may produce “a significant yet modest deterrent effect on crime.” Weisburd et al further note, however, that “it is not clear whether other policing strategies may have similar or even stronger crime-control outcomes. In turn, the level of (stop and frisk) needed to produce meaningful crime reductions are costly in terms of police time and are potentially harmful to police legitimacy.”

In other words stop and frisk might have a modest deterrent effect if it’s practiced specifically in crime hot spots though those same effects can potentially be achieved through other, less controversial, means.

Weisburd’s study found “significant impacts on crime within small areas and across short time periods.” The crime drop at the micro level did not directly lead to a massive drop in crime though as Weisburd estimates “that in the peak years of (Stop and Frisk)in NYC, almost 700,000 (stops) would lead to only a 2% decline in crime.”

So establishing the strategy may have had a role in some of New York’s decline in crime let’s turn to the rest of Senator Kennedy’s comment. That comment basically amounts to three underlying ideas: 1)Stop and frisk would be an effective tool for reducing New Orleans gun violence; 2) it’s the only thing that will work in New Orleans, and; 3) it won’t amount to racial profiling.

Closer examination of all three ideas, however, shows that none reflect the reality of the New Orleans environment.

Stop and Frisk Would Work Here

Successfully implementing stop and frisk in New Orleans would face numerous serious impediments (let’s ignore all the major moral and constitutional issues for just a second), the most galling of which is that New Orleans simply lacks the manpower to implement such a strategy.

NYPD brings over 35,000 officers to the table to implement a strategy like this while NOPD had 1,081 officers as of late June. That means there are roughly 414 sworn police officers per 100,000 New Yorkers but just 275 per 100,000 New Orleanians.

The impact of NOPD’s manpower decline since 2010 is well worn territory, but it cannot be stressed enough that stop and frisk is the exact kind of proactive policing that NOPD is doing substantially less of these days.

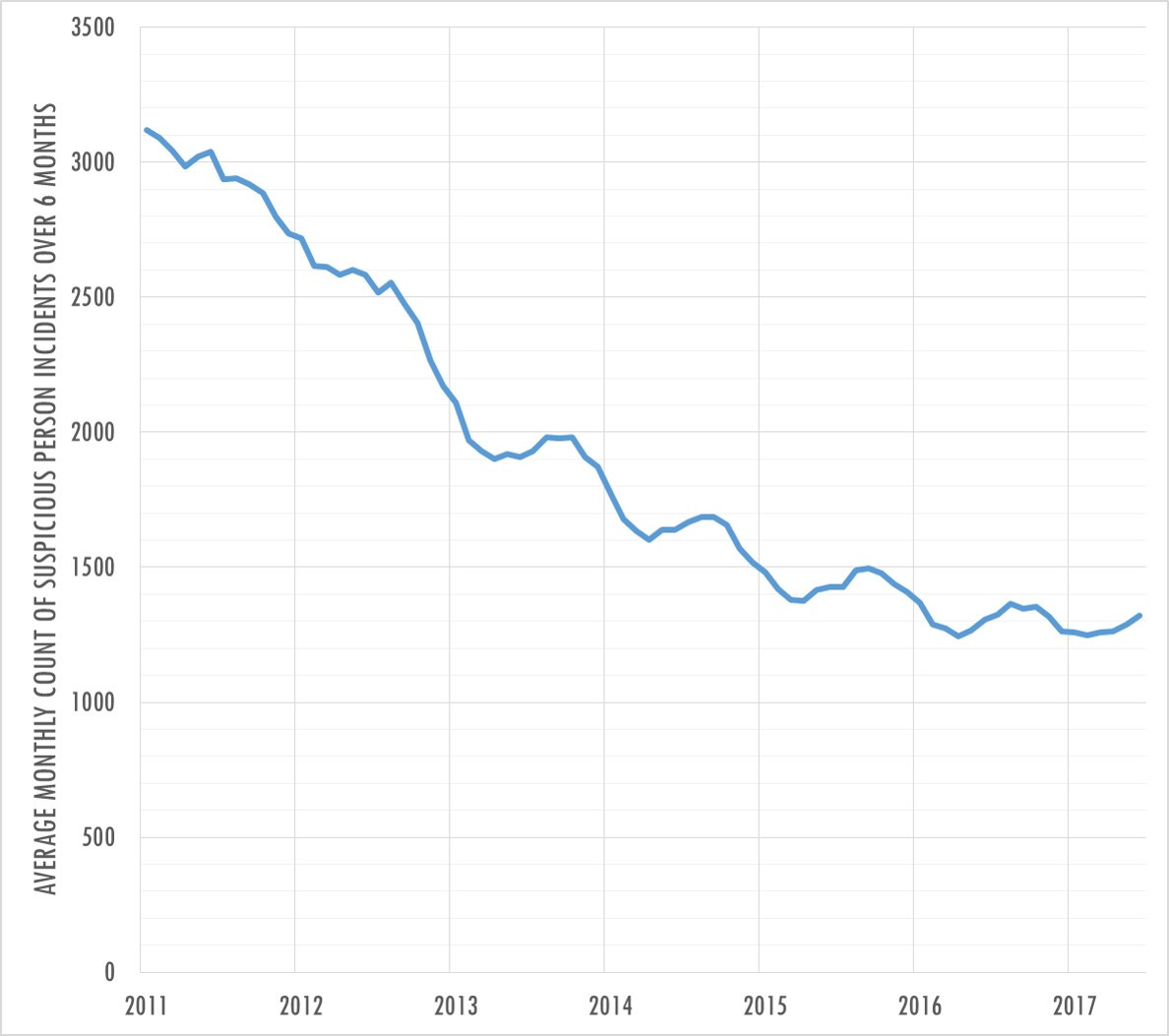

The below two charts highlight how much NOPD proactivity has fallen over the last few years as a large part due to manpower.

First is the average monthly count of suspicious person Calls for Service over 6 months since the start of 2011. This change correlates very strongly with the change in NOPD manpower over that time and has largely leveled off as NOPD’s sworn manpower has leveled off at between 1,050 and 1,100 officers. There are undoubtedly those who would blame the consent decree for this change in policing, but the decree was not agreed upon until July 2012, was not approved by a judge until January 2013, and the monitor was not selected until August 2013. The timeline simply doesn’t fit.

There are undoubtedly those who would blame the consent decree for this change in policing, but the decree was not agreed upon until July 2012, was not approved by a judge until January 2013, and the monitor was not selected until August 2013. The timeline simply doesn’t fit.

Another measure of proactivity that has fallen considerably is “self-initiated” incidents. These are incidents that the officer creates by investigating by himself or herself. NOPD did not begin tracking these until late 2013, but there is a similar decline in these types of incidents over the last 2.5 years.

“Successfully” implementing stop and frisk in New Orleans would require a level of manpower that NOPD simply does not currently have and will not have for the foreseeable future. Even if the strategy was fully constitutional and without severe moral qualms, executing it at a level at which it proves beneficial here would prove to be extremely difficult.

“It’s the only way I know left”

Senator Kennedy has been busy in Washington so I’ll forgive him for not being completely up to date on the literature of what works and what doesn’t in reducing gun violence. But there are strategies known to sustainably reduce shootings and murders, and Kennedy is simply wrong claiming that stop and frisk is basically our last resort.

Thomas Abt wrote my favorite meta-review of what works in reducing gun violence, conveniently titled ‘What Works in Reducing Community Violence’. Abt notes the below six “Elements of Effectiveness” in the violence reduction initiatives that he reviewed.

Stop and frisk may have some proactive elements, but it lacks nearly everything required of an intervention program aimed at reducing gun violence.

The Senator seems to be suggesting we are out of ideas, but New Orleans has a model for reducing gun violence that has already been through the rigors of an academic review! Nicholas Corsaro and Robin Engel reviewed NOLA for Life in 2015 and found that:

The development of a multiagency task force, combined with unwavering political support from the highest levels of government within the city, were likely linked to high programmatic fidelity. Organizationally, the development of a program manager and intelligence analyst, along with the use of detailed problem analyses and the integration of research, assisted the New Orleans working group in identifying the highest risk groups of violent offenders to target for the (Group Violence Reduction Strategy) notification sessions. The impacts on targeted violence were robust and consistent with the timing of the intervention.

That right there is almost all of the essential elements for a successful program. The city’s gains of 2013 and 2014 may not have been sustained over the long run, but that doesn’t make the theory of how to sustainably reduce gun violence any less valid. Senator Kennedy is basically suggesting throwing the baby out with the bath water just as you’re about to get the temperature just right.

“When it’s done correctly, race has nothing to do with it”

Senator Kennedy’s comments suggest that there won’t be a racial element to stop and frisk in New Orleans, but in New York there certainly was.

In 2011, the height of the strategy’s implementation in New York, black men made up 55.1 percent of individuals stopped despite making up just 10.1 percent of the city’s population.

Black men were frisked more often than average with 59.5 percent of stops of black men leading to frisks versus 52.2 percent for the rest of the population in 2011. Yet black men were less likely to get arrested with stops leading to arrest with 5.7 percent of black men and 6.2 percent with everyone else.

Will Stop and Frisk NOLA be aimed at the French Quarter? If so then race may not come into play, but manpower will be stretched even thinner by a crowded Quarter. And the program’s effectiveness will be virtually nil due to the fact that gun violence simply doesn’t happen often in the French Quarter.

Or will Stop and Frisk NOLA be mainly targeted in gun violence hot spots as Weisburd suggests it must be in order to work. If so then it would be targeted in neighborhoods like Central City (72 percent black), the Seventh Ward (87 percent black), or Pines Village (95 percent black).

Conclusion

Simply put, there is no use for Stop and Frisk in New Orleans. Not now, not ever.

It cannot be effective under the city’s law enforcement operating capability for the foreseeable future. It would not be effective unless it was targeted against the city’s hyper concentration of gun violence. If it was effective it would be a morally wrong step that would reverse many (if not all) of the gains that NOPD and the city have made to reduce incarceration and reform how NOPD engages with the community.

Finally, implementing Stop and Frisk in New Orleans would ignore all of the evidence and past experience that tells us what we need to do to sustainably reduce gun violence here. Just because the effects of past efforts wore off does not mean we should ignore the lessons of their initial successes.

New Orleans and NOPD have come a long way in the last half dozen or so years. The prison’s population is falling, citizen satisfaction with NOPD’s performance is high, and we know more about what works in reducing gun violence than ever before. Crime is unacceptably high, but that doesn’t make Senator Kennedy’s comments or underlying sentiment any more correct.

Leave a Reply