Reader Alex Elkins sent me a tweet the other day asking if I’d read Joseph Fichter’s 1964 report on NOPD’s handling of arrestees. Not only had I not read the report, I hadn’t even heard of Joseph Fichter before. Fortunately Mr. Elkins was kind enough to send me a copy of the report and allow me to post it for anyone to download here.

Joseph Fichter was a Jesuit priest originally from New Jersey who came to New Orleans in 1947. Fichter taught and did research in Loyola’s sociology department for 44 years. He died in 1994 and got an obituary in the New York Times.

The full thing runs 65 pages (from page 10 to page 75 of the above PDF) and consists of findings from interviews of arrestees, police officers, and other people associated with the criminal justice system (like lawyers). The report is largely focused on what’s right and what’s wrong with how New Orleanians are arrested & booked. Ultimately Fichter settles on three main recommendations:

- Replacing the “present scattered system of precinct lock-ups” with a central lock-up.

- Establishing 24-hour magistrate services.

- Steps need to be taken to improve NOPD’s professionalization when handling arrestees and other citizens.

Parts of the report are familiar to readers in 2017 highlighting the similarities in policing in both eras. Interestingly, the study was undertaken about a decade after a Metropolitan Crime Commission investigation found rampant corruption and wrongdoing within NOPD (see the early parts of this dissertation for a nice summary of the fight against NOPD corruption in the 1950s). NOPD’s corruption in the 1950s was considerably different from the issues plaguing the department right after Katrina, but Fichter’s look at an improving department 10 years after major scandals took place is very similar to our own current viewpoint.

In introducing the report, Fichter quotes NOPD Superintendent Joseph Giarrusso as saying: “The citizens of this community expect top notch service from their police officers, and rightly so, but the citizens also have a very serious obligation to cooperate in every manner possible.” This quote would have fit in as well in 2017 as it did in 1964 as would Giarrusso’s comment that “the public image of the New Orleans Police Department is largely a reflection of the manner in which the citizen observes and interprets the behavior of law enforcement officers.”

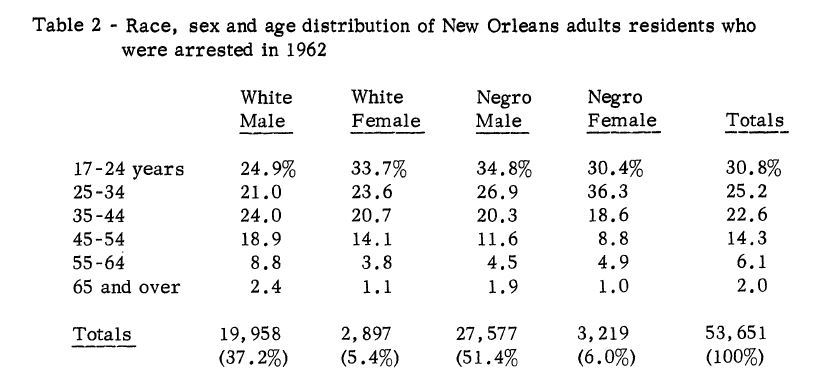

Another similarity between the 1960s and today is that men in general (and black men specifically) make up a disproportionate percentage of arrestees. Fichter provides the below graph that finds men made up nearly 90 percent of 1962 arrestees.

Compare that to the below table which is an approximation of 2016 arrestees in New Orleans that I made using the city’s Electronic Police Report database. To make this approximation I took all incidents which were cleared by arrest and identified the offender’s race and gender. I found that about 76 percent of all 2016 arrestees were men and 59.1 percent were black men.

Of course what is jarring about this report are the differences between the 1960s and today. While most interactions with NOPD in the 1960s appeared to be positive/professional, Fichter has sections dedicated to reports of racist & abusive language, informal bribery, sexual harassment and physical abuse of arrestees. The section on physical abuse, for example, is summed up in the below paragraph.

These sections can be difficult to read and I hope I’m not naïve in believing behavior in today’s NOPD is world’s apart from this version of the police force.

In all Fichter’s work is the earliest example I have seen of an effort in New Orleans to use data to evaluate policing. As a New Orleans crime analyst I found it extremely interesting although nothing in the report is particularly groundbreaking to an audience in 2017.

Leave a Reply